Twenty-eight year old Sam Mills wasn’t exactly pretty to look at. He had only one eye, one usable eye, anyway. A bar-room fight in the silver and lead mining town of Eureka in the mid-to-late seventies had seen to that. He was “a very bad character,” says retired Elko historian Howard Hickson.

But his death was 138 years ago. And Mills was a minority in a time when Christian sentiments about race didn’t count for much — some say they don’t count for much nowadays either. My guess is, when an angry man threatens you in a lead-town bar, saying, “You black son of a bitch. I’ll teach you to think you’re as good as a white man” — words preserved by another Elko County historian, now long gone — you’re going to defend yourself. You may even end up in a Carson City prison, which of course, Sam Mills did.

I mention Mills because he was the first African-American to be hanged in Nevada, and the first man of any color or distinction to be legally executed in Elko County. I was so fascinated by the tale when I first heard it that I made his story a big part of my story, in my book True Believer.

The fourth in a series of Nevada-based Westerns, True Believer relates the early history of Elko, Lamoille and Wells while spinning an imaginary tale of murder, mayhem and unrequited love in the eastern shadow of the Ruby Mountains. Read it and you’ll meet real-life Elko resident Jim Clark, who owned the Depot Hotel on Commercial Street, in 1881. You’ll also visit Wells’ first permanent building and bar, the Bulls Head Saloon, made only of railroad ties.

Read any of the W. W. Ronin Westerns — there are four in print, a fifth to be published by summer 2015 — and you’ll see Nevada in in a way you never thought you would or could.

When Mills was executed in 1877, at the end of an Elko County rope, he was 24 years old. But he wasn’t put to death for his barroom brawl in Eureka. He was hung for accidently killing his best friend. Here’s the rest of the story.

Sam Mills was making the best of his life, working as a cook at a hotel in Halleck Station, just outside of Elko. He kept his nose clean and out of other people’s business. He expected the same of others he met. But one hot summer day, in the course of a heated argument with the female proprietress of the Deering Hotel, Mills was fired. During the ensuing argument, a man named Webb knocked him to the floor, and Mills pulled a knife. Whether it was in self-defense or not, we’ll never know. But Sam left angry and without incident.

Still, when the story got out that Mills had snapped, local folks were concerned.

Webb and Deering ran to a nearby saloon, where Mills had armed himself with a handgun. Hearing of his friend’s difficulty, Billy Finnerty volunteered to talk Mills down before things got out of hand. As Finnerty stepped through the saloon doors, Sam Mills shot him dead.

Finnerty, it’s remembered, shouted “Someone pray for me! I’m gone!” I’d like to think that Mills did just that, before stealing a horse and galloping out of town.

On June 10, 1877, just three days after he killed his best friend, nearby ranchers Myron Pixley and John Maverick found him hiding in a Lamoille Canyon haystack. My book fictionalizes the events of that day, and the evening prior, while reporting Mills’ last moments in an Elko jail, where he is remembered to have sung hymns and told fortunes. But the outcome was the same.

In the judge’s instructions to the jury, obtained by this writer from the Elko County Clerk’s office in April of 2015, District Judge John H. Flack — who was colorful man in his own way, laying down dimes for drinks that cost a quarter, and sometimes dozing on the judicial bench — counseled the jury with fifteen specific instructions: “Murder is the unlawful killing of a human being, with malice afore thought,” Flack said. “Malice is that deliberate intention unlawfully to take away the life of a fellow creation which is manifested by external circumstances capable of proof.” A unanimous jury convicted Sam Mills of first-degree murder. He was sentenced to death. The district court’s decision was unanimously upheld by the Nevada Supreme Court in November.

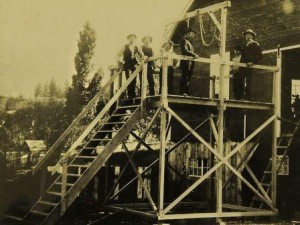

On December 21, 1877, Sam Mills was led to his death on a platform constructed just for that purpose. His hands, arms and feet were bound. A black hood and executioner’s rope were placed around his head and neck. When the lever was pulled, Sam Mills hung there for a good twenty minutes until his heart stopped. His neck had not broken because his body was too thin and too light to bring the requisite weight to do the hangman justice. Ten minutes after that he was taken down and pronounced dead.

Mills’ final words were, “I am a poor colored man with no friends nor money. If I had money and a good lawyer I could have got clear.”

The long road toward redemption is sometimes a hidden one. For many felons, it begins in a hotel restaurant.

A few years ago, I was on a ride-along with a Washington County sheriff’s deputy just outside of Portland, Oregon. I asked why cops seemed to congregate at certain restaurants over against others. “We don’t want felons spitting in our food,” he said. “Some cooks harbor a grudge.” I’ve taken a different point of view of restaurants ever since.

But there’s something about Mills’ death that still haunts me.

Mills grew up in the South as a child of slave parents. At the time of his trial and execution, his parents were too penniless to attend, living in Atkinson, Kansas. If Sam Mills had had money, and been white, would he have “got clear?”

Sources:

Elko County Criminal Records — County Clerk’s Office, Elko, Nevada — Jury instructions.

Howard Hickson, http://www.gbcnv.edu/howh/SamMills.html, accessed 04.14.15

Edna B. Patterson and Louise A. Beebe, Halleck Country: The Story of the Land and Its People, University of Nevada Reno, 1982.

Edna B. Patterson, Louise A. Ulph and Victor Goodwin, Nevada’s Northeast Frontier, Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1991.