The old door shook. It wasn’t his intent to harm anything.

Fact is, the once-reverend W. W. Ronin wouldn’t think of making light of the buildings that had given him succor over the years—initially in Greensboro, Pennsylvania where he was in training, and later in Wichita, Kansas as the second rector of the St. John’s Episcopal Church, when it was still made out of logs and situated between the confluence of two sometimes over-flowing rivers.

There was still something sacred about religious places, even if he didn’t embrace the faith they sometimes contained.

The church wasn’t just about “the people,” as he used to say while preaching, one hand on the lectionary, the other searching for a Bible in the event his people asked an unexpected question or two over the meal that many times followed services. Church was the building, too, though he didn’t understand that at the time.

He lifted his knee up to his chest and pushed again, the bottom of his foot—the ball, actually, not the heel as it dissipated too much force to use his boot that way—and the old wooden doors, crafted from pine planks harvested in the Sierra mountains, just up the Kings Canyon toll road he figured not that it mattered, splintered into pieces like the old man’s leg caught under the wheel of an errant coach from Benton’s Livery on Carson Street last week.

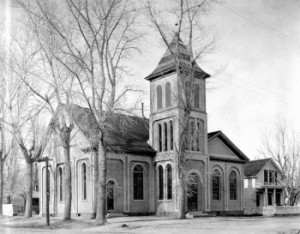

The door swung back and forth, its lock shattered, shards of it rolling lifelessly across the entry way of the building, erected in 1861, before Nevada was even a state. Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain’s) brother, Orion and his wife Molly attended there, though Clemens was now dead, having died a year ago, about the same time he began to wonder if there was anything real at all to the Protestant convictions he once proffered as an Episcopal priest on the American frontier.

He dumped the shorter of his two Colt handguns over the back of his holster, until it was level, and then slowly extended it forward into the midnight darkness of Nevada’s oldest sanctuary, as long as you didn’t count the Mormon meeting place in Genoa, or the Catholic church which was actually finished before the Presbyterians were, though the Calvinists had started earlier but ran out of money. The 1873 Colt Peacemaker had a custom four-inch barrel, shorter than most, and had been given him by the Wichita congregation when he expressed his desire to see the “Wild West,” he called it, before it disintegrated into a sun-bleached pile of buffalo bones and dead Indians, though he hoped at the time that neither would happen despite the prognostications of railroad men who swore that “modernity,” as they called it, would someday link city to city and even coast to coast.

It was a funny gift for a preacher man. But he had grown fond of the gun, even come to appreciate its tool-worthiness in pulling the human refuse out of towns like Santa Fe and Salt Lake, and nearby Reno too, now that he lived on the eastern slope of the Sierra mountains in the Silver State’s capital city and was working as a bounty-hunter of sorts, though he liked to think of himself more as a detective.

Goddamnit, he breathed, as he broke another toe on one of the old pews that had been moved in the pastor’s recent effort to move himself closer to his congregation.

The pale green building was rectilinear in shape, a center aisle pushing up toward a Protestant altar where literally nothing happened religion-wise, not like in a Roman Catholic Church or even an Episcopal building, where the death of Christ was enacted literally over and over again. The Presbyterian congregation, unable to see past the expanse of stained and painted pine pews facing the front, and the Jennie Clemens’ memorial Bible sitting on the communion table like the altar it wasn’t—had been twisted sideways so that the people sat shallow-like, looking toward the stained glass that painted the north side of the slump-stone building with colored lights and biblical characters from stories hardly remembered by the city’s fathers and mothers who sat there thinking they were doing an important thing. The prison quarry had provided the building’s stones and labor, though no one talked of it anymore, saints sitting alongside of sinners, though few talked about that either, save in a careless women’s circle or men’s day out, when the church’s congregants pulled up out of control shrubbery or planted easy-to-care-for spring flowers.

It wasn’t like his fugitive didn’t know he was in there, what with all the noise he was making after he’d collapsed the front door into a pile of Sierra-grown firewood. He’d make a donation, he figured, sometime after they hauled the next Christmas tree to the front of the sanctuary from the Woodfords or wherever. The opening would serve them well for a while.

“Listen, you son of a bitch,” he said out loud, thinking it odd he felt so comfortable cursing in the house of God, though he was certain that if Jesus attended there—the Galilean, in his seamless dress, all perfect and free, having suffered an excruciating death on a cross at the hands of church goers of all things, though it hardly surprised him, now—the Jewish savior would say the same thing, to more than a few people hiding out on top of the pews where his escaped felon was likely hiding beneath. “Stand-up, you snake. Or I’ll strike you down where you lie.”

The church was still, as he imagined every Carson City church to be on a mid-week evening around midnight, save maybe the Baptists and the Catholics, too, who were all kinds of active, with group meetings and middle of the night services he didn’t understand because a Christian sanctuary was supposed to be a good deal quieter than that, where a man could muse about spiritual things, or important things anyway, like he sometimes did at Saint Peters when George Allen was rector, “Old Mutton Chops,” he called him until the morning Mutton Chops found out and betrayed that he, Ronin, had a nickname, too.

“Fair enough,” he said, “it’s William, then. Shall I call you George?” and the reverend looked at him sort of uncomfortable like and nodded, knowing there was no way in hell a former priest was going to refer to another priest by anything other than his first name.

There was a quiet stirring toward the east side of the building where a small shed served, he guessed, as the church’s sacristy as he’d never been in the sanctuary, only the manse next door where a series of pastors had lived. The first he’d met was a supply preacher out of Virginia City. “Hands up, you jackass. You’re lucky I don’t plug you where you are.”

“Ronin?” the voice called out.

“Reverend?” the former reverend W. W. Ronin said.

“I heard a noise,” the pastor said.

“Reverend, there’s a devil loose in the church tonight.”

A hearty belly laugh sounded out from the sanctuary’s side door. The church’s pastor lit a lamp on a small table in sight of the door, where a communion set was sitting—its cup and a tall stack of bread plates, on which to serve “the body and the blood of Christ,” as most Christians said. It was a sacrament he thought was no longer necessary to celebrate. Being a good man was good enough. Hell, being a man was hard enough. He figured a man or woman’s actions didn’t matter a whole hell of a lot if God was good and great and everything the church thought God to be was true, anyway.

“Son, there’s a devil loose in every church,” the Reverend Woods said. “If you think there’s a special one here hiding out, I guess we ought to turn the lights on.” Woods pushed a couple of buttons and the sanctuary began to glow. “Ronin, there’s no one here but you and me,” he said. William Washington peaked down the length of pews, south to north, as the new preacher had set them, cattywampus to the right and proper teachings of the Episcopal Church.

“No, there is not,” he replied, holstering his sidearm and nodding, as a sort of silent apology to breaking down the doors of the Presbyterian Church in Carson City. “And the doors, reverend…”

“Yes, my son?”

“I’ll attend to them tomorrow.”

“Come on by the parsonage,” the new reverend said, who followed the Reverend McClain, who succeeded the Reverends Fairbairn, Rice and Fraser, who had only stayed a couple of months each before preaching elsewhere. “Let me make you lunch. There’s a problem I’d like your help with, if you’re still working the dark side of the bench.”

“The bench, sir?”

“The sinners’ bench, Ronin, the confessor’s bench, where liars, thieves and other sinners wait for the grace of God to head their way.”

“Well, that could be any one of these pews, Reverend. Or any number of people, too.”

The preacher grabbed his belly and began to laugh again. “That’s the point, son. I’ll see you about noon.”

From The Rage and the Reckoning, a Western I work on, from time to time, in-between other projects. I thought it might be nice to see a piece on the Presbyterian Church in Carson City, where I served as pastor and head of staff for almost ten years, in the late eighties and early nineties, 1980s and 1990s, that is!